For many communities, developing a bike plan is the first step in creating or expanding their bicycle infrastructure network. Here at Toole Design, we’ve worked on hundreds of bicycle plans throughout the United States, from small rural communities to large urban areas. In our 16 years of bike planning, we’ve found that there are some common problems that can adversely affect a bike plan’s progress. Avoid the 10 most prevalent pitfalls by following some advice from our bike plan experts:

1. Lumping all types of bicyclists, trips, and goals into a single plan

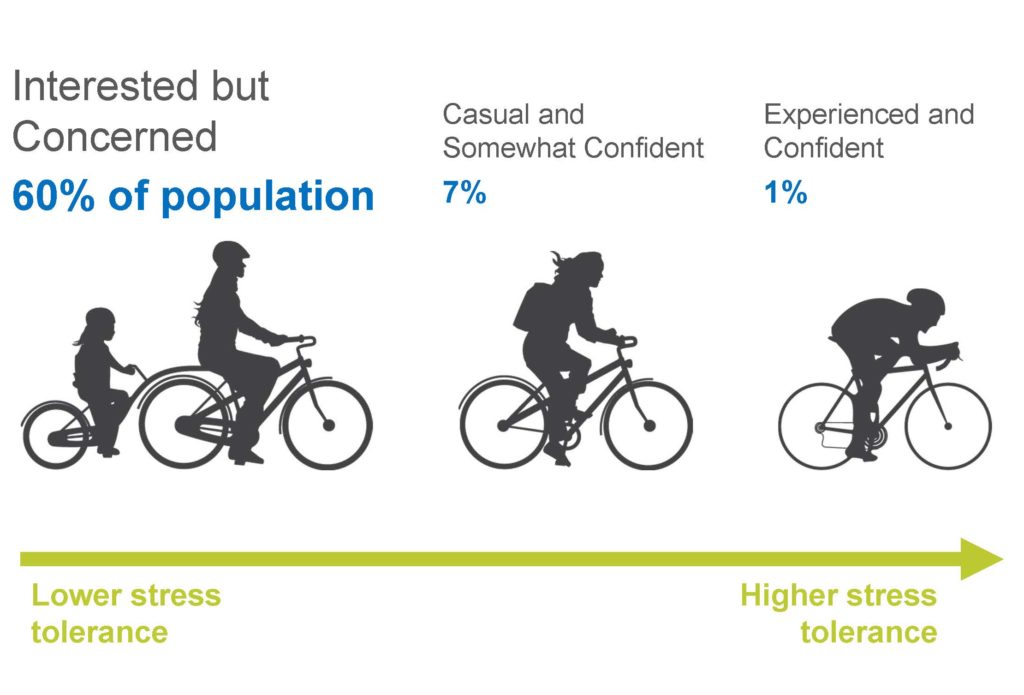

Bike plans are not always clear on their audience (avid bicyclists? interested but concerned riders?), what types of trips are prioritized (commuting, recreation, both?), and how the network should operate (should it cover the entire city? focus on major destinations?). If this remains unclear or if a community tries to address all interests equally, the plan will likely be ineffective.

Clarify your priorities. Determine your community’s priorities early in the process. Explore the pros and cons of these choices, and once you decide on the best fit for your community, try to stick with it throughout the plan. Ask what you want the plan to accomplish and what success (and failure) looks like.

2. Sticking with traditional methods

When developing bike plans, we sometimes revert to planning for bikes in the same way we plan for cars—with a focus solely on major trip generators and attractors. Traditional demand analyses have their place in bike planning, but if they’re all we focus on, we miss important considerations for why people choose to bike.

Instead, plan for the unique characteristics of bicycling. Bike plans will ultimately be most effective if they directly address bicycling’s unique characteristics: the importance of bicyclist comfort and stress, shorter average distances, the impact of hills, and the various motivations that members of your community have for bicycling.

3. Obsessing about data

During the planning process, stakeholders can sometimes get stuck in data quicksand—always looking for and analyzing more data. While data is certainly necessary for understanding your community’s conditions and characteristics, not all data adds value to a bike plan. Collecting, sorting, and analyzing data that is not essential to your plan’s stated goals and priorities can be a drain on the project budget.

It is both more effective and efficient to be wise about data analysis. Identify your goals of the plan and evaluate the data most relevant to addressing them. Staying focused on the priorities identified in your plan will help you efficiently identify and review the right data.

4. Creating unwieldy technical committees

Many public agencies lean towards creating large technical advisory committees, inviting anyone that may directly or tangentially be involved with bike planning. Overly large committees can slow down the decision-making process and delay the development of the bike plan.

Instead, keep technical committees focused and nimble. Make a list of the most critical decision-makers to include in a small committee and invite everyone else to focus groups or other tailored outreach events.

5. Letting the usual suspects do the talking

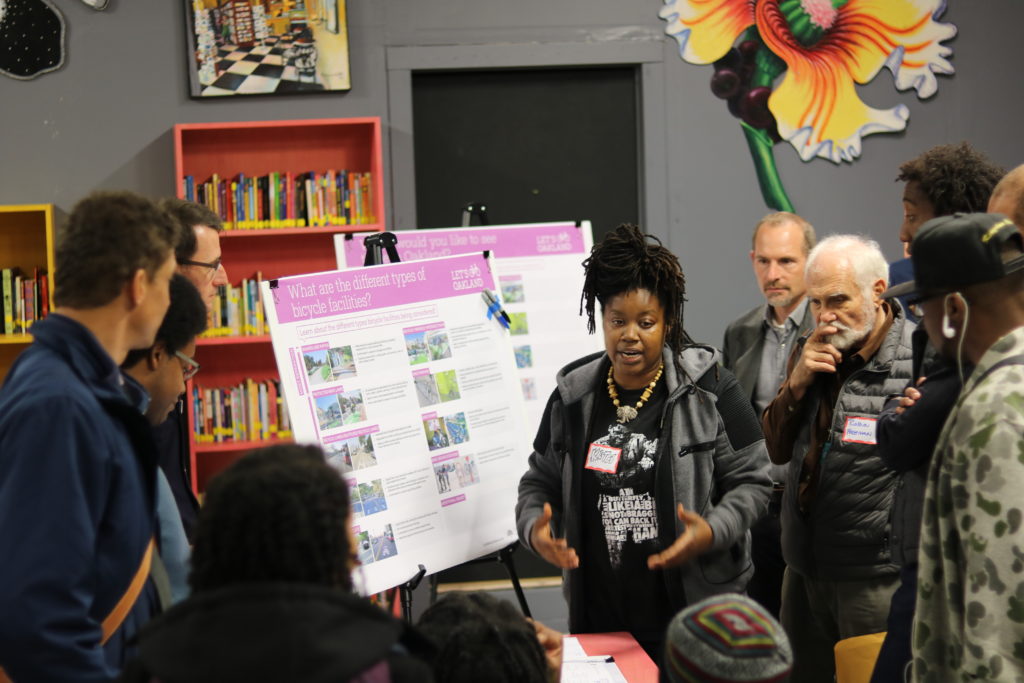

For many years, public engagement for bike plans was pretty cookie cutter: host a public meeting, receive input from those who showed up, and call it a day. While simple, this method often attracts those who are already the most passionate—for and against—a plan, and frequently does not reach underrepresented communities or those who have been historically excluded from planning processes. We also miss out on the input of families, non-bicyclists or infrequent bicyclists, and people with limited transportation choices, who may be no less passionate about what’s at stake.

Cast a wide net with your engagement strategy. Be intentional about your outreach goals and do your homework on the people, groups, and organizations you need to connect with. Take time to understand the different perceptions about bicycling that exist in your community and frame your message accordingly. While biking is a priority for some people, it’s a symbol of gentrification to others. Partnerships with community-based organizations are essential in understanding local priorities.

Bike plans are increasingly being framed in terms of community health, equity, safety, and/or economic development—a message that reaches a wider audience. By taking the public engagement as seriously as the technical work, we do a much better job of serving the entire community rather than only those who currently bike.

6. Approaching networks without the necessary flexibility

Rigid network route definition can lead to problems during implementation. For most plans, street-level route recommendations are necessary to determine the proposed bike network. However, actual constraints along each street might not become apparent during the route definition process. There are also times when, once we select a street as part of the bike network, we become inflexible in adjusting routing should it be appropriate.

Instead, make sure to understand the constraints before developing route recommendations. We recommend doing this in one of three ways:

- Define the network at the corridor level with fuzzy, less-defined lines to indicate that the corridor can be served by multiple parallel routes and the option with the fewest constraints should be selected during the implantation phase.

- Define the route at the street-level, supported by an engagement and implementation approach for concept planning that has route confirmation as a first step.

- Make plan corridor recommendations flexible enough that if, during implementation, it becomes clear that a parallel route is preferable, that alternative can be implemented instead of the original segment.

7. Promoting projects that are easy rather than effective

It’s common for bike plans to prioritize projects for near-term or long-term implementation based on ease of construction and availability of funding. This approach doesn’t always create a network that people actually want to ride on, and it often results in disconnected, impractical routes that lack community support.

Instead, identify a short list of signature projects to create a “backbone” network. Prioritize the construction of 3-5 high-impact, high-visibility projects to kick-start the development of your initial network. These transformational projects are more likely to garner early public support and ridership, and they often lead to strong support for the continued build-out of the proposed network. To create a network, these high-profile projects should be connected to one another by existing low-stress streets or easier-to-implement projects. You can then enhance these connections over time.

8. Missing the bigger picture

Bike plans can fall into the habit of focusing purely on where bikeways should go, neglecting larger issues that also deserve attention. These issues might be physical barriers, such as competing street uses like on-street parking, loading zones, turn lanes, transit stops, utilities, and trees. They may also be people-oriented or political, like weak community or political support, complex relationships between government entities and communities or groups, and lack of staff or budget resources.

In either case, the planning process should recognize and resolve competing interests. Understanding the public, political, and municipal landscape from the beginning of the process can help create a more realistic bike plan and identify pathways for building support.

9. Making recommendations without an implementation strategy

Many bike plans lose steam when it comes to the final chapter, lacking a detailed strategy on how to effectively implement the plan’s recommendations. What’s often missing is a clear picture of who is responsible for implementation, the timeline, and possible funding sources. The entities and individuals tasked with implementing the plan (public works staff, maintenance staff, and elected officials) are often left out of the planning process, which results in internal skepticism or projects that get delayed or cancelled entirely.

To avoid this, create specific implementation strategies and involve those responsible for implementation throughout the planning process. Invest the time and effort needed to create a specific implementation strategy and include those who will fund and build the projects from the start. Take a lead from Vision Zero Action Plans, which often include a clear timetable for what should occur, and identify exactly who must do it.

10. Not measuring what matters

Bike plans often list performance measures that are based on data that is already available rather than recommending measures that truly gauge the effectiveness of the bike plan.

Be sure to develop effective performance measures. Realistic, easily-quantifiable measures are the most effective, and they should reflect your community and the goals of the bike plan.

Also, keep it simple! Too many performance measures, like too much data analysis, can result in information overload and make it difficult to develop concise conclusions on the effectiveness of your bike plan.