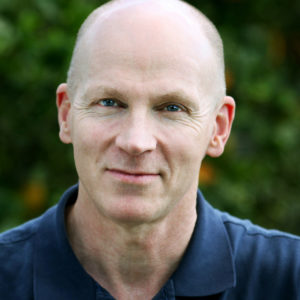

From an early age, Ian Lockwood’s sister wanted to know, “Why do you always have to try to change things to be better?” Half a century later, Ian Lockwood, Professional Engineer, is still a change-maker, transforming communities across North America by empowering people to imagine a future where people come first.

From an early age, Ian Lockwood’s sister wanted to know, “Why do you always have to try to change things to be better?” Half a century later, Ian Lockwood, Professional Engineer, is still a change-maker, transforming communities across North America by empowering people to imagine a future where people come first.

Lockwood, a Livable Transportation Engineer, joined Toole Design in 2015. He has been challenging conventional wisdom in his chosen profession since the early 1990’s when he cut his teeth fighting the expansion of a rural highway (US 50) in Virginia, proposing instead a series of traffic calming measures (including roundabouts) that were almost unheard of at the time.

“After leaving the Canadian Army, I actually wanted to be a police officer, but didn’t have the perfect unaided vision that was required,” he recounts. “So, I went to school to study engineering and the most interesting path to me was civil engineering. During my studies, I learned about traffic calming in Delft (NL) and I thought ‘this is the future,’ only to discover that virtually no-one in North America was doing this kind of work.”

In fact, Lockwood discovered there was only a small cadre of people discussing traffic calming. A couple of years later, traffic calming was “a thing” and an ITE Committee wanted to provide guidance. “The only problem,” he recalls, “was that everyone had a different idea about what traffic calming was! The first thing we had to do was come up with a definition we could all agree on.”

Fast forward 30 years and Lockwood is calming traffic on a grand scale. “Cities have been evolving for thousands of years,” he explains. “People have always been the most important element in city-building right up until the last 75 years when we decided to put cars first. Since then, we’ve built highways that have damaged and divided communities, destroyed glorious parks and natural places, and blighted waterfronts in city after city. I’ve come to realize that removing highways from cities, isn’t a technical issue, it’s a moral issue and a political issue.”

Lockwood shows me a long list of highway removal projects he has been involved with over the years. There are some losses on the list, some in progress, and some wins. Some projects, like the South Pasadena Freeway (I-710), had to be killed several times. “We nick-named it the Zombie Highway because it was so hard to kill. However, we think it will stay dead now.” And there are some transformative projects underway including places such as Oakland (I-980), and Buffalo (SR-198). Several of these projects feature in the Congress for New Urbanism’s Freeways without Future report.

In 2016, he was part of the US Department of Transportation’s Every Place Counts Design Challenge which helped four communities, “build ladders of opportunity, reconnect neighborhoods, revitalize communities, and empower residents to have a meaningful voice in transportation decisions” all of which had been destroyed by the highways.

When I ask how Toole Design’s core values, centered around ethics, equity, and empathy, guide his work as an engineer, he says, “I knew Toole Design would be a good fit for me because those are my values too. In places like Oakland, Dallas, Houston, Nashville and others, the equity issues are inescapable. Black and immigrant communities have been destroyed, isolated, and polluted by highways because they simply weren’t valued by people with power. Highway removal is a chance to undo racist policies and wrongheaded decisions of the past.”

More recently, Lockwood has been working with the City of Brampton, just north of Toronto, to change a proposed highway project, called the GTA West, into a boulevard. “I was asked to critique a plan for the 4,000-acre development area around the proposed highway. The plan showed, two big interchanges, sprawl development, and no connection to a major passenger rail corridor that bisected the site. I found it ethically impossible to help make the highway and sprawl plan ‘work better.’ It was simply the wrong plan considering the climate, environmental, and health issues facing society. Our boulevard-based, active transportation-oriented-development (aTOD) plan will provide better outcomes for health, quality-of-life, investment, infrastructure costs, environment, and equity; it will do much less damage, and knit the community together rather than tear it in half.”

“Empathy and equity are particularly relevant for highway removals,” he continues. “The restored area will become more valuable, walkable, and desirable after the a highway is removed. Strategies need to be in place so existing residents can stay, (i.e., not be displaced), build wealth, and have access to opportunities in their own community. Highway removals are good but should not be followed by displacement; so well-crafted and concurrent programs, plans, and reparations are needed.”

This year’s Engineers Week theme of “Imagining Tomorrow” perfectly captures Lockwood’s career to date. “We are problem solvers,” he says. “We identify problems, and we fix them. But we must always remember why we do the work we do, and that should always bring us back to our values and the community’s vision of what the place ought to be like tomorrow. Engineers are so fortunate; we get to make a difference in people’s lives. We can imagine tomorrows with communities, and build them. We are change-makers.”