We are celebrating 20 years of Toole Design this year by taking on the topics that will define our industry over the next 20 years. We hope to spark collective action to create safer, healthier, more just communities. In our previous article in this series, we took on the complex topics of gentrification and displacement. Next up: climate change.

Toole Design has spent the past 20 years dedicated to transforming our transportation system to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, making it possible to take transit, walk, and bicycle. While we are proud of the work we’ve done, we, like many others in our industry, spent the summer in growing horror as fires, floods, and extreme temperatures fueled by climate change resulted in disasters throughout the world.

We are facing unprecedented catastrophes and instability caused by climate change, and it is increasingly clear this will intensify in our lifetimes. Certainly, our children face a far different future than we ever imagined.

Our values of ethics, empathy, and equity compel us to speak up because:

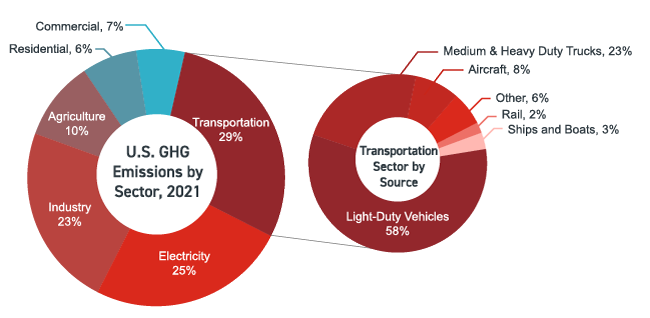

- We know what the causes of climate change are. The transportation sector is responsible for up to a third of greenhouse gas emissions.

- We know what the solution is: we must dramatically reduce vehicle emissions while preparing the built environment for extreme weather events.

- We know much of this will impact the world’s poorest, most vulnerable populations first.

First, We know full well what the problem is.

The simple fact is that in North American communities, there are too many cars driving too many miles to be sustainable. Our industry has engineered North America into a dangerous car dependency that makes even simple, short trips difficult or impossible for people who walk and bicycle.

This is not only bad for the environment and our survival, but it’s also manifestly unsafe, inequitable, and economically unsustainable for people living in our communities today.

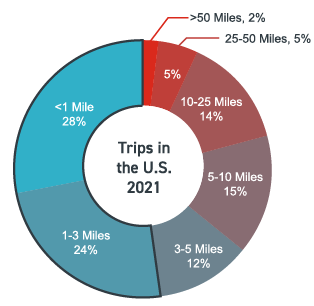

More than 50% of trips in North America are just three miles or less. This should be the perfect foundation for a functional active transportation system, and yet more than two-thirds of those trips are made by car today. We must help the public — and our elected officials — understand the value of rapidly re-engineering our transportation system to make it comfortable and convenient to walk, bike, and use transit, especially for these short trips.

Second, we need to stop making things worse.

To start the turn-around, we must stop doing the things that perpetuate this auto-dependency. We must clearly state that the approaches we have taken for the last 70 years are not going to make things better. In fact they will make them worse. We have trained the public to demand auto-centric solutions with false promises of congestion fixes.

Sadly, even the best examples of new pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure can be overwhelmed by a single highway expansion or interchange project. In the Richmond, VA area, for example, Toole Design is working on the Fall Line, a 43-mile regional trail from Ashland to Petersburg that will link seven jurisdictions and provide active transportation connections to tens of thousands of people. This project presents a tremendous opportunity to serve those short trips and reduce auto-dependence. The price tag is roughly the same as one new highway interchange that we know will generate more car traffic, create impenetrable barriers for people in heavily populated areas, and further lock in car dependency. Projects like the Fall Line are relatively rare, while hundreds of highway interchanges are under construction at this very moment in nearly every city in the United States and many in Canada.

Third, We need to act.

We must make it easier and quicker to take action. Agencies are revising design guidance and finding strategies to quicken the delivery of infrastructure that supports transit, bicycling, and walking. A rapid implementation strategy is needed in every community, tailored for their unique project delivery context. Cities like Houston, Austin, Philadelphia, and Seattle, as well as state agencies like Ohio DOT and Massachusetts DOT, are proving this is possible.

Of course, trying to change entrenched cultural and societal norms is hard work. We all know the challenge of trying to take away a travel lane or a parking space, and how easily we accept over-built roads and more capacity for cars. Our biggest obstacle in tackling climate change in the transport sector isn’t conflicting science, or lack of a compelling need or available solutions. It’s making the right, often difficult, choices.

Every project is an opportunity for positive, even if incremental, change.

We have to remember that every project is an opportunity for positive, even if incremental, change. Approximately 20-50% of any given urbanized area is covered in asphalt. Every project should seek to reclaim or repurpose as much of this space as practical to address modal inequities, improve the environment, and provide landscaping and trees. These strategies are essential to reduce heat-island impacts. We know that green infrastructure can make streets more resilient and encourage walking, biking, and transit instead of driving… but our engineering standards often prevent their use. These are things we can and must fix now, so that every time we break ground on a new infrastructure project, it helps to repair and restore our environment.

While the consequences of climate change can at times feel overwhelming, we should feel privileged to work in a profession that can help mitigate this crisis and make a difference by reducing emissions and building greener landscapes. We have the power to act, and the time to act is now. We must seize this moment and lead.

Share your ideas

What strategies are at the top of your list for implementing more climate-resilient transportation solutions? Share your thoughts on LinkedIn or send us an email.

Where Do Electric vehicles Fit In?

Electric cars have their place. They are certainly better than internal combustion engine cars in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. However, they come at an enormous environmental cost, as, for example, mineral extraction for lithium batteries depletes resources and damages ecosystems. Electric cars offer no benefits in terms of health, land use, and access — and due to their increased weight, they likely have worse safety outcomes. Possibly the greatest threat posed by electric cars is that they allow people to think they are THE answer and that we can otherwise carry on as we are.