We are in historic times, with many communities reconsidering the conventional transportation approach of emphasizing efficiency and vehicle mobility above community-driven goals. Earlier this year, U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg announced $3.33 billion in grant awards for 132 projects through the Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods Grant Program. Building upon the Reconnecting Communities pilot launched in 2022, these grants are moving U.S. communities one step closer to a reconnected urban fabric.

Through intentional, equitable, and community-informed design, these reclaimed spaces hold the potential of connection, opportunity, and prosperity for people who have been denied these things for too long. To unlock that potential, we need to address the history that got us here and take a holistic approach to reimagining urban highways.

The Advent of Urban Highways

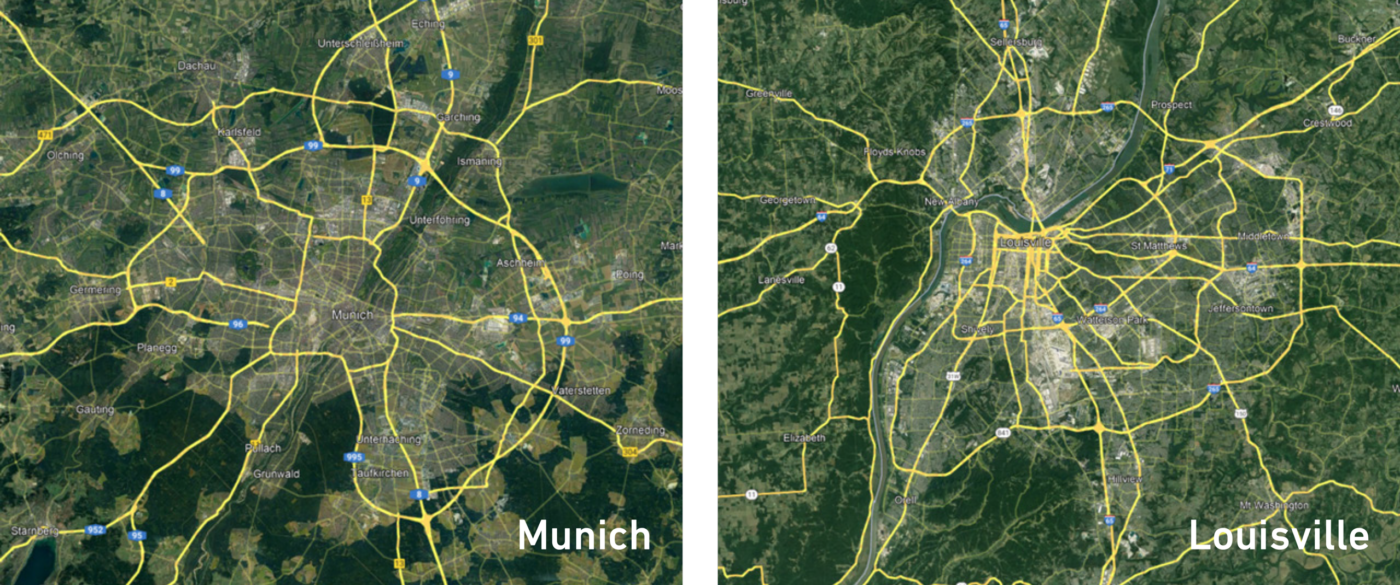

In the 1950s, as motor vehicle ownership grew exponentially, Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. This set in motion a system of highways connecting cities to each other that was inspired by Germany’s Autobahn system. Today, the nearly 47,000 mile Interstate highway system provides connections to population centers, support for interstate commerce, and critical infrastructure for interstate freight movement.

While Eisenhower never envisioned highways extending into urban areas, decision makers at the State and local level started building them nonetheless, encouraged in part by the incentive of 90% Federal funding and the perceived promise of urban “renewal.” By 1968, 1,500 miles of urban Interstate were officially added to the system. Whether Eisenhower would approve or not, urban highways have become a hallmark of the American city.

Feeling the Effects

While urban highways may have decreased travel time for people driving through cities, they destroyed homes, businesses, and ways of life for many people living within those cities. The harm did not end with displacement and dispossession. People who remained in areas divided by highways have had to grapple with the chronic harms of physical and psychological disconnection, air and noise pollution, disinvestment, increased traffic violence, and, ironically, the least transportation access and choice.

Communities nationwide pushed back, but highway revolts were largely only successful for white neighborhoods with more of a political foothold. Despite vocal opposition, few Black and brown communities had the political resources or connections to prevent forcible location and community destruction. Rondo, La Calle Ancha, Roxbury, Claiborne Avenue, Buttermilk Bottom, Boyle Heights: these are just a few of the predominantly Black or immigrant neighborhoods that were razed in the name of urban renewal. These projects were undeniably racist — planners at every level of government often wielded highway construction projects as a tool to remove “urban blight” or reinforce lines of segregation.

In the 1960s, for example, the I-75/I-85 highway in Atlanta tore through “depressed” but vibrant Black communities including Buttermilk Bottom, Sweet Auburn, and Old Fourth Ward. The construction of the so-called “Downtown Connector” displaced an estimated 24,000 people and separated historic Black neighborhoods from downtown jobs and services.

This story has been repeated in hundreds of communities across the country.

The Reconnecting Communities program reflects a growing realization that highways, despite playing an important role in long-distance travel, defense, commerce, and evacuation, have done long-lasting damage in the heart of cities. They have destroyed neighborhoods, created unhealthy environments, lowered property values, eroded the tax base, and enabled sprawl.

Now, as many urban highways are reaching the end of their lifespan, instead of rushing to repair them, we should question whether they meet the transportation needs and vision of 21st century cities.

Highways already Reimagined

While the topic of highway transformation may feel new, many urban highways have been stopped, removed, or relocated over the past half-century. The City of Portland stopped the planned Mount Hood Freeway in 1968 and physically removed Harbor Drive in 1973. The elevated West Side Freeway in New York was removed by 1989, making way for a burst in real estate activity and tree-lined public spaces. The Embarcadero was removed from San Francisco in 1991 (after being damaged by the Loma Prieta earthquake), and the Park East Freeway in Milwaukee was removed in 2003. Other highways were relocated, such as the Central Artery in Boston, which was relocated underground. Other urban freeways were redirected or relocated to Interstate loops.

Cities and states should not balk at the idea of highway transformation as an idealistic, unrealistic, high-cost/low-reward endeavor. For many stretches of urban highways, transformation will not only connect people, but also — as examples have shown — will yield economic benefits, support climate resilience, and make cities stronger. And in other cases, the cost of repairing or replacing aging highway structures is so expensive that removal is a far more cost effective option.

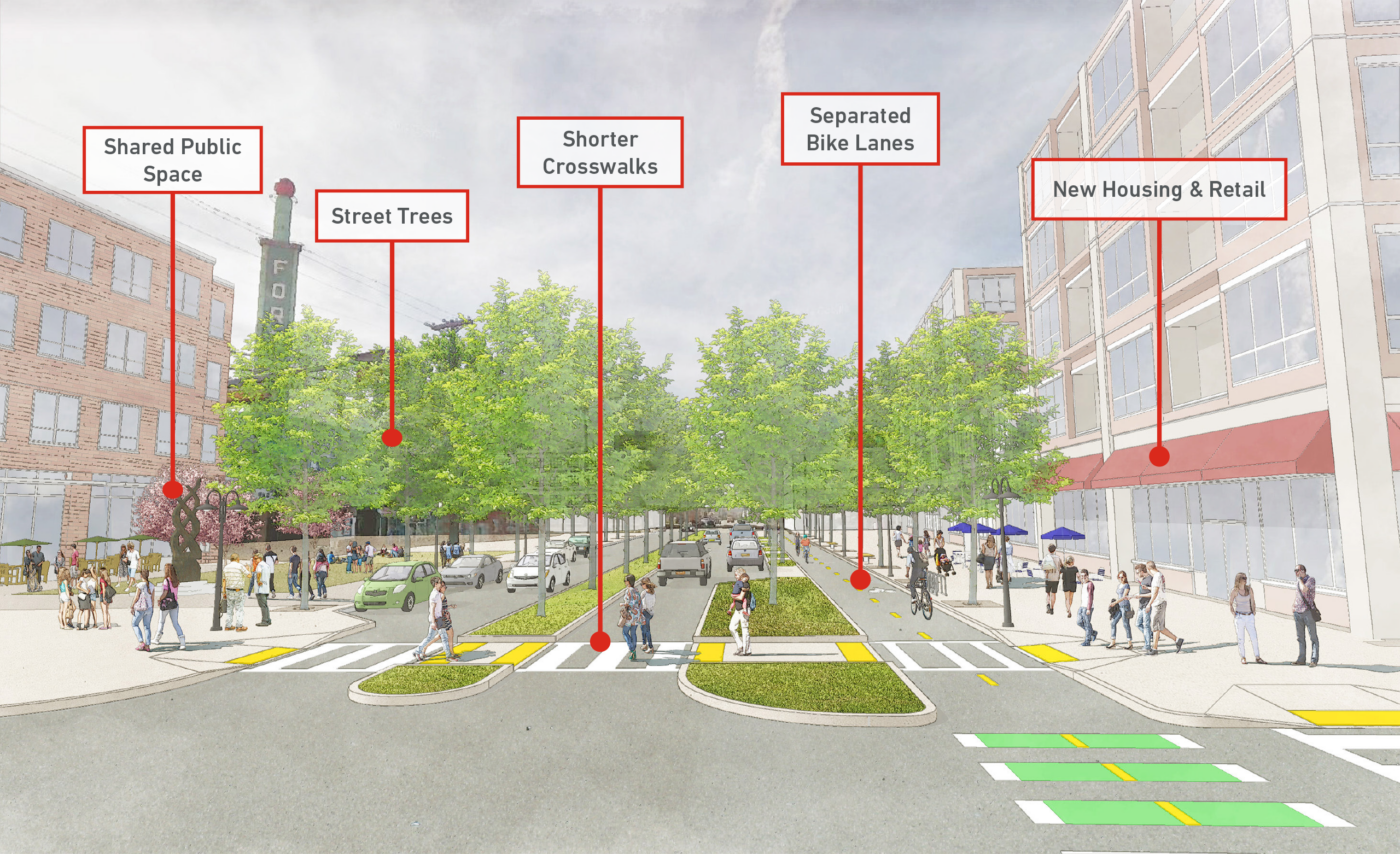

Some projects have the potential for economic development and investment that far outstrips the cost of removal. In 2021, the eastern section of the Inner Loop in Rochester, NY, was transformed into a boulevard with improved pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure. The City of Rochester spent $22 million to fill in the Inner Loop and reclaim 6.5 acres of land from the highway, which has yielded $229 million in development over its first two years.

The Path Forward

To harness the highway removal momentum, repair the harm that has been done in divided communities, and restore the social and economic vibrancy of these areas, it is important to plan and design with intention. And as with all projects, we need to infuse the process with the values of ethics, equity, and empathy. At Toole Design, we welcome the shift toward people-centered solutions and are proud to apply our technical expertise to transformative projects throughout North America that aim to reconnect communities.

While we cannot undo the damage caused by decades of urban highways, we can re-stitch our cities together for a more connected, equitable future — such as in Atlanta, where we are working to “cap the Connector,” reconnect Downtown, catalyze affordable housing and transportation access, and create 14 acres of urban greenspace.

Toole Design has engaged with public agencies and organizations across the country to reimagine highways and reconnect communities for over 15 years. With Coalition for a New Dallas, for example, we developed the I-345 Framework Plan. The Plan lays out the potential costs and mobility benefits of a surface street option and a depressed highway option, projecting each option’s impact on economic development, job creation, environmental justice, quality of life, and transit connectivity. To learn more about the efforts to reimagine I-345 in Dallas (and a more detailed account of highways that have been removed from U.S. cities), check out Megan Kimble’s fantastic new book City Limits.

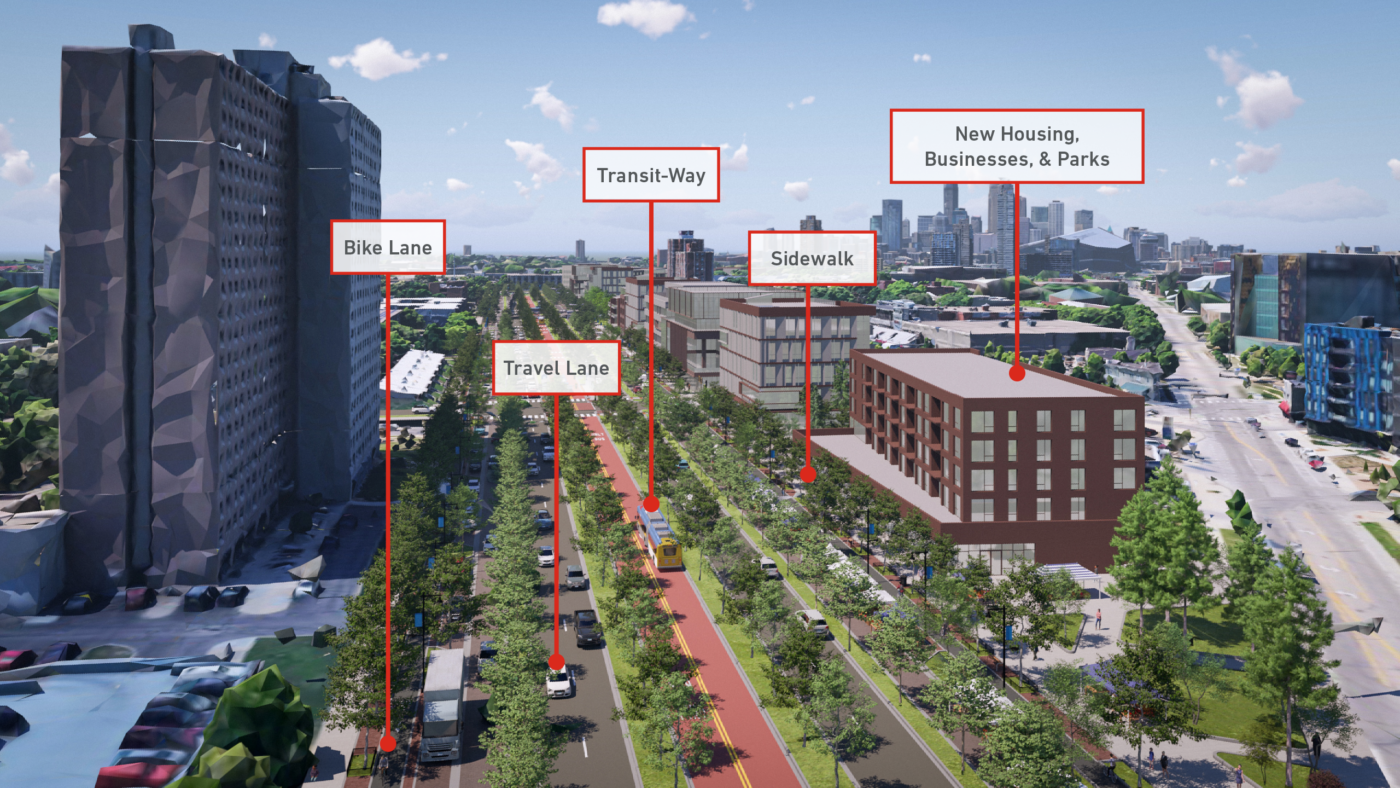

We also worked with Our Streets Minneapolis to reimagine the I-94 corridor between Minneapolis and Saint Paul as a multimodal, human-scaled boulevard. The recently published Reimagining I-94 Report examines usage patterns and future travel demand considerations, evaluates boulevard alternatives, and aims to deepen public understanding and enrich the Rethinking I-94 conversation. (Hear more about this project — and a helpful explanation of highway removal and mitigation terminology from Toole Design’s Ian Lockwood — in this episode of the Streets.mn podcast.)

Stitching communities back together is more than a feat of engineering — it is a creative and collaborative design endeavor that begins with political will. Simply removing parts of highways will not bring fractured neighborhoods back to life nor magically create equitable and sustainable development. Cities must invest in holistic neighborhood repair and proactively address the new problems that come with increased public and private investment. Displacement protections for legacy residents and housing stability and affordability programs should go hand in hand with any such project to create a diverse, mixed-income community.

Clearly there is much work to be done to fully shift the collective consciousness toward the alternatives of dense, mixed use, walkable neighborhoods supported by transit and safe bike access. But the progress being made is heartening. The Reconnecting Communities program is a testament to the movement’s success so far.

We know the ingredients to create thriving, integrated urban spaces. That’s why Toole Design never has been — and never will be — in the business of highway building or highway widening.

Let’s harness the energy around rethinking urban highways to inaugurate a new era of reconnection and creative city building. Click the link to learn more about our experience and expertise: Highway Reimagining at Toole Design.