This article was originally published in Michigan Planner magazine and was authored by Director of Design Bill Schultheiss, PE and Engineering Group Manager Mariel Colman, PE, AICP.

We teach kids that red means stop, long before they learn numbers or the alphabet. But across the U.S., red lights often mean “pause briefly, then turn right.” For nearly 50 years, right turn on red (RTOR) has been a staple of American traffic operations. It gained traction in 1975 when Congress, reacting to the OPEC oil embargo, required states to adopt RTOR and other energy conservation measures, believing it would conserve fuel with little downside.

But is RTOR effective and harmless? Closer examination reveals a more nuanced reality: one that is driven by inertia, not evidence.

The Myth of Efficiency

RTOR is often assumed to improve traffic flow. But this benefit depends on specific, often unmet, conditions: no through-traffic blocking the right lane, no pedestrians in the crosswalk, a safe gap in traffic, and an unobstructed view. In practice, many drivers roll into the crosswalk to see around obstructions, then stop scanning for pedestrians or cyclists approaching from their right. The result is a risky, complicated maneuver.

To assess the traditional traffic modeling approach that is used to justify RTOR as a time saving technique, Toole Design’s traffic engineering team set up a generic intersection using typical urban characteristics in Synchro to test different signal timing scenarios (RTOR restrictions, cycle length, etc.). The results: RTOR may provide a very small reduction in delay for motorists, but only when there are sufficient gaps in traffic. But how are gaps present in the busiest time of day for motor vehicle trips? When gaps are present, it’s more a sign of inefficient signal timing than a need for RTOR. Shorter signal cycles or alternative timing strategies often deliver better performance than RTOR, for all road users.

The Highway Capacity Manual says it’s “difficult to predict the RTOR flow rate because it is based on many [8+] factors that vary widely from intersection to intersection.” An accompanying graphic shows only minimal differences in delay between right turns that did and did not permit RTOR. Contrary to the popular statement “the model says…”, traffic models reflect biased assumptions and is based on limited, fixed data. They are not a lens into the future and do not account for user preference to change routes, modes, or destinations. Or in this instance, all the other factors beyond traffic gaps necessary to make RTOR possible, making even Toole Design’s testing likely rosier than reality. Yet, traffic engineers input data into the model and treat the readouts as facts.

Denying Right of Way and Increasing Dangers to People Walking and Bicycling

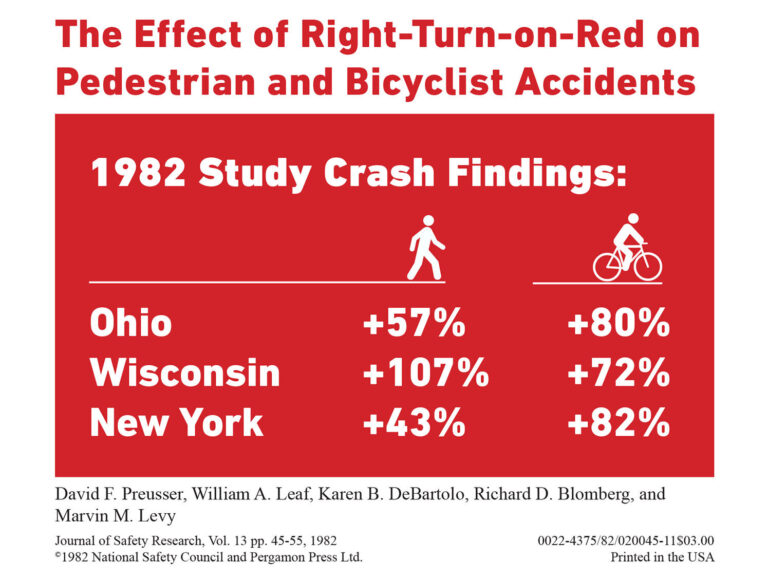

It has long been believed that this policy is relatively harmless. Complicating this question is the fact that research on this issue is limited because of the rapid, widespread application of this policy in 1980. However, in 1982, the U.S. Department of Transportation funded a study of the impact of RTOR analyzing data before and after the widespread adoption of RTOR. The researchers looked at the rate of pedestrian and bicyclist crashes in three states (New York, Ohio, and Wisconsin) and two cities (Los Angeles and New Orleans).

Researchers noted the rapid onset of crashes: “It was as if the number of right-turning accidents shifted to a new level — 50 to 100% higher than the old level — and stayed at that level throughout the data collection period,” introducing a persistent safety hazard.

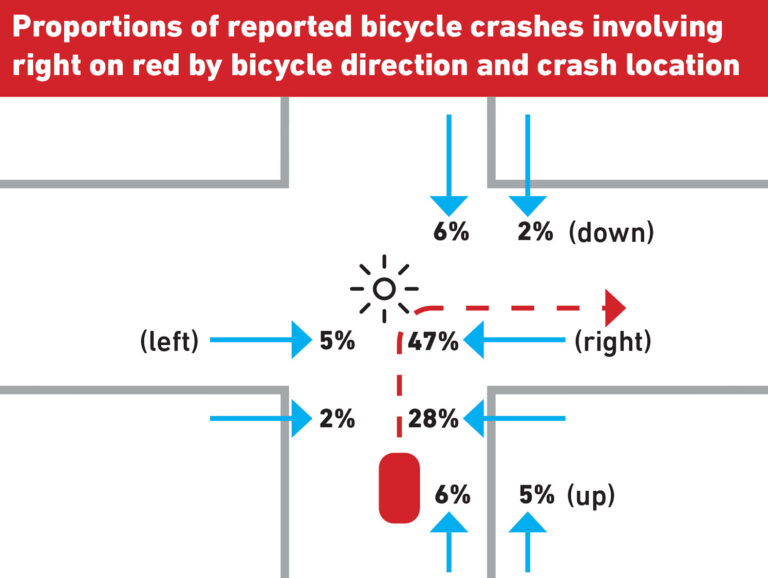

RTOR also prioritizes motorist movement over pedestrian and cyclist mobility. When drivers roll into the crosswalk to turn, they deny vulnerable users their right-of-way. Pedestrians must cross in blind zones or behind vehicles — sometimes outside the crosswalk — heightening their risk and reducing their comfort. These conflicts can discourage walking and biking altogether.

Higher Hoods, Higher Speeds, Higher Risks

Since the late 1990s, vehicle design changes have made RTOR even more dangerous. In 2022, 75% of U.S. vehicle sales were SUVs and trucks. These vehicles are larger, heavier, and have taller hoods and higher front blind zones, often obscuring anything within 10–15 feet ahead. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety has found SUVs and trucks are overrepresented in pedestrian right-turn crashes compared to smaller vehicles.

Compounding this is a culture of speed and aggression. Advertisements glamorize rapid acceleration, like Dodge’s “Never Lift” campaign: “Keeping a foot firmly planted on the gas pedal.” And some electric vehicles (EVs) now gamify 0–60 mph times. Even though sports cars represent a small share of the market, nearly all EVs offer faster acceleration than most gas-powered sports cars available. This performance allows drivers to accept smaller gaps when turning, increasing crash risks, especially when paired with larger blind zones.

These factors are contributing to a national public health crisis, with pedestrian and cyclist deaths reaching 20-year highs. “I didn’t see them” remains a common refrain in police crash reports, echoing the findings from the 1982 study. If Vision Zero is the goal, municipalities must address these recurring failures.

Things Are Changing

Planners and engineers can’t redesign the entire vehicle fleet, but they can redesign intersections and re-evaluate operations. Professional codes of ethics demand that transportation practitioners prioritize the “safety, health, and welfare of the public.” RTOR policy falls short of that mandate. In response, some cities are limiting or eliminating RTOR as part of broader Vision Zero efforts. Washington, DC; Cambridge; Raleigh; Ann Arbor; and Seattle have adopted large-scale NTOR policies. In DC, a pilot at 74 intersections led to a 92% reduction in failure-to-yield incidents and a 97% drop in vehicle conflicts. These benefits came with “minor impacts to traffic operations,” according to a 2020 ITE Journal article. NTOR, the city concluded, offers a low-cost safety tool for jurisdictions with limited budgets.

While citywide bans may not be feasible everywhere, a corridor- or district-based approach using NTOR can still support a safe system framework. Applying NTOR consistently — near campuses, downtowns, or high-foot-traffic zones — can improve safety, reduce confusion, and build community support. Strategic NTOR zones align with equity goals, improving access for those walking and biking in historically underserved areas.

A Safer Way Forward

Vision Zero requires more than rhetoric — it demands action to eliminate known risks. RTOR is one such risk that can be eliminated. As vehicle mass, speed, and acceleration increase, vulnerable road users face growing threats. RTOR, once implemented in the name of convenience and efficiency, now poses unnecessary harm.

It’s time to shift course. Removing RTOR is a clear, proven way to prioritize people over vehicles and to build streets where everyone can move safely.