The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that physical inactivity – getting no exercise beyond the exertion of daily living – contributes to 1 in 10 premature deaths and $117 billion in health care costs in the U.S. every year. CDC’s response to this crisis is Active People, Healthy Nation, a national initiative “to help 27 million Americans become more physically active by 2027.” The campaign is based on the simple premise that increased physical activity improves public health across a range of conditions, from diabetes to hypertension to asthma.

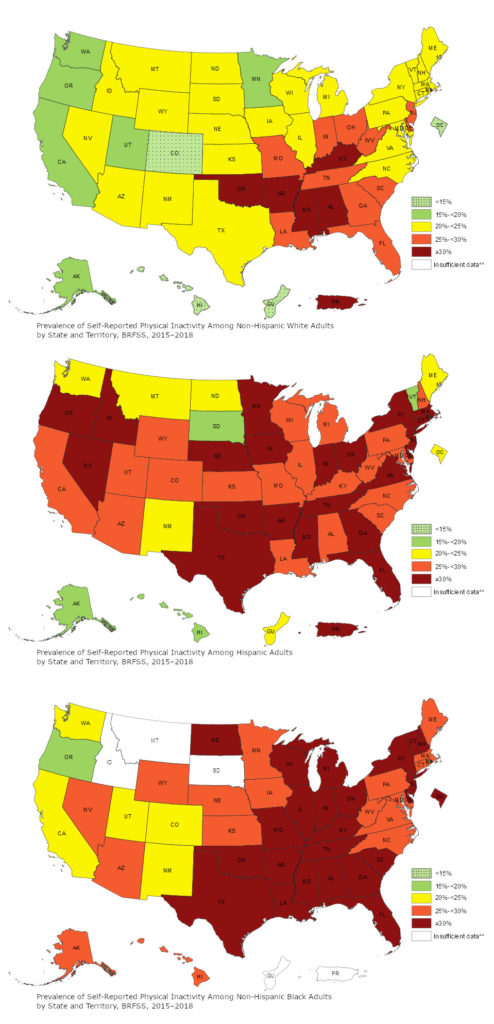

Significantly, the prevalence of inactivity rates differs dramatically along racial and ethnic lines. CDC notes that “in the majority of states, non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics had a significantly higher prevalence of inactivity than non-Hispanic whites.” Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System show that, in most states, Black and Latinx adults were nearly 1/3 more likely than their white counterparts to report engaging in no leisure-time physical activity for a full month before they were surveyed.

These high levels of physical inactivity, and their disproportionate impact on populations of color, didn’t develop by accident. For decades, transportation spending has focused on streamlining automobile travel, while making it more dangerous for residents to get around their neighborhoods without a car. The built environment solutions that CDC recommends – protected bike lanes, special bus lanes, comfortable and accessible transit stops, frequent crossing opportunities, median islands, accessible pedestrian signals, and curb extensions – are far rarer in majority–minority neighborhoods. These areas have instead been carved up by highways, disconnected from transit, and targeted for industrial development and “urban renewal.”

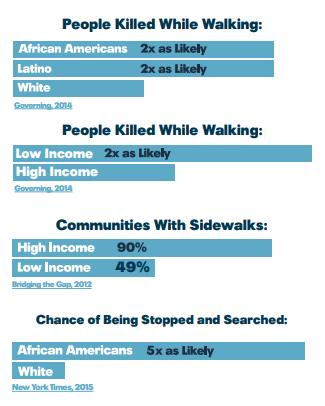

These disparities put CDC’s goal of increasing physical activity among people of color on a collision course with another public health challenge. Deaths and serious injuries among pedestrians, bicyclists, and other non-car users have increased year-over-year for nearly a decade. This predictable outcome of a car-centered transportation system is most acute in urban areas, where people of color are more likely to make up a larger percentage of the population.

CDC’s stated goals also seem at odds with the priorities of other government agencies. As Smart Growth America noted in its Dangerous by Design 2019 report, 18 states set goals for non-motorized user deaths and serious injuries in 2019 that were higher than the previous year. Federal Highway Administration funding guidelines don’t contain any penalties or incentives that might encourage states to work harder to lower the number of casualties among people walking, biking, or rolling in a wheelchair.

CDC properly focuses on equity as a foundation of its strategies to increase physical activity, and acknowledges that “inadequate infrastructure for active transportation exists in many low-income communities and communities of color.” However, the report treats these infrastructure failings like a natural phenomenon – sort of like referring to crashes as “accidents,” as so many transportation agencies (and the media) continue to do. It fails to acknowledge the role of policy choices and systemic discrimination in building active transportation infrastructure in some neighborhoods while neglecting others. And it fails to grapple with the ways that our transportation priorities have focused on shaving seconds off car commutes, to the exclusion of public safety, health, and well–being.

Another resource from Smart Growth America, The State of Transportation and Health Equity, describes the problem plainly: “creating an equitable transportation system will require stakeholders from across levels and disciplines to improve the system both from within and from outside.” It calls for taking the difficult but necessary steps to correct historic neglect, including equitable allocation of resources, improving diversity among transportation leadership, and prioritizing historically underrepresented communities in transportation decision-making.

Individuals and organizations that work in the transportation industry are beginning to have these difficult discussions and are looking for ways their projects can do more good in historically underserved neighborhoods. In the February issue of the ITE Journal, Toole Design’s Jennifer Toole, AICP, ASLA, Tamika L. Butler, Esq., and Jeremy Chrzan, P.E., PTOE, LEED® AP make the case for centering equity in the work of transportation design and planning, and offer suggestions for developing an equity-focused approach in organizations and in the world at large. The special issue also features practical advice from Charles Brown, MPA, CPD of Rutgers University on implementing an equity approach.

With Active People, Healthy Nation, CDC has diagnosed an injury and recommended treatment for the symptoms, without really being able to identify the source of (or a cure for) the underlying trauma. Until we reckon with the systemic priorities that perpetuate inequality, and begin to address the disparities in resources those priorities have caused, true equity in public health outcomes and access to opportunities for physical activity will remain out of reach.