It’s time to throw out “journey to work” as our primary transportation measure. We’re already exposing and replacing some of the basic tenets of transportation planning and engineering, like relying on the 85th percentile to set speeds and using motor vehicle level of service to justify pointless highway expansion. We should do the same with our assumption that transportation equals getting to and from work every day.

There’s more to transportation than just commuting

People who’ve worked in the active transportation field for a while have long put an asterisk by the data that is used by state and local agencies across the country as the basis for most travel models, analyses, and planning activities. The decennial Census and annual American Community Survey asks people how they get to and from work – but it asks only for “primary mode”, so if you walk or bike to transit it’s only the transit part of the trip that counts. The same goes for trips by people who might ride their bike once or twice a week or during warmer months; those trips never get counted.

The long-form Census always came out in March, which isn’t the best month for walking and biking to begin with. Commuting trips are also typically the longest trip people make every day, and generally the trip where punctuality, carrying capacity, cleanliness, and neat hair are considered essential. None of these things are exactly conducive to walking or biking.

Once you start digging into these issues, you realize that there’s another flaw: commuting trips are in no way the only trips that people take. We ride to the grocery store after work, walk to church or to meet with neighbors, jog for exercise; and more. In fact, commuting actually accounts for less than 20% of all the trips that people make.

Coronavirus has made this even more clear

The dramatic shifts in behavior caused by the coronavirus have thrown a dramatic new light on this reality. In recent tweet, Barb Chamberlain at the Washington State Department of Transportation asked why traffic levels were almost at pre-pandemic levels even though so few people were back at work…well, it’s because people still need to get things done. Going to school, shopping, exercising, running errands (like medical visits), and visiting friends and family make up the overwhelming percentage of daily trips.

Despite this, our transportation models and thinking still revolve almost exclusively around the journey to work.

Of course, thanks to the global coronavirus pandemic more than 30 million people are still unemployed in the United States and have no work trip to make. Tens of millions of others are working from home and are not likely to be making that routine daily commute for some considerable time in the future, if ever. And, let’s not forget that relying only trips to and from work for our transportation data automatically ignores everybody under 18 and over 65 to begin with.

What does all this mean for transportation planners? I think it means that the most important trip we should be thinking about isn’t the 11-mile each-way single-occupant car commute (if it ever was). It’s the local errand – the kind of short trip that doesn’t, or shouldn’t, require getting in a car and driving.

Two Toole Design projects that illustrate this concept

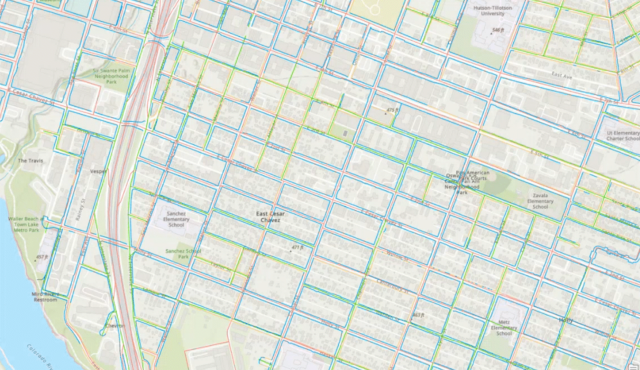

Two projects I’m working on in the DC metro area bring this home. The roadways of Tysons, VA (below, left) have been defined for decades by the daily influx of 100,000+ workers each day; but in today’s world, they look massively overbuilt and ripe for rebalancing. By contrast, the Bowie, MD area (below right) on the eastern side of the metro area has seen a much less dramatic decline in traffic because it is a heavily car-dependent bedroom community – the issue in Bowie is that even things well within walking distance or a short bike ride away from home are practically impossible to walk or bike too because of lack of safe access. Shopping centers are literally fenced or walled off from neighborhoods; roads are unsafe for biking and are missing crosswalks and sidewalks.

It seems quite likely that as we move forward, people are going to make fewer trips than before, which is probably good for our collective environmental footprint. More importantly perhaps, those trips are more likely to be short, close to home, untethered to a traditional commute trip, and don’t require any particular clothing or grooming standards (other than a mask) upon arrival. This ought to mean walking and biking are much more competitive and realistic choices – and certainly healthier and more fun – provided the infrastructure is there to welcome people and make it the easy choice as well.

One more example from a bit farther south

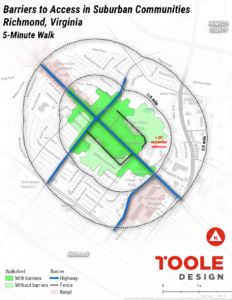

I also see these barriers in my own Richmond, VA area neighborhood. I live no more than a five or six minute walk (literally 600 steps) from the front door of a prominent national book store chain but have to go around a fence and cross a major road to get there…things which I am guessing most of my neighbors don’t care to do.

As the map below shows, a lot of people live even closer as the crow flies but cannot get directly to the nearby stores because of a creek, needless perimeter walls and fences (left), six-lane roads (right) with 45mph posted speed… you get the idea. Most people will likely drive, and once they are in the car, maybe they’ll go somewhere else instead.

We don’t know what’s going to happen with people’s trip-making habits and what shifts in travel patterns and modes are going to be possible. However, as in so many other ways, events of the past 6 months have brought our focus back to some simple truths that we’ve been overlooking for a long time. Even in the suburbs, most trips are quite local, and a lot of people would choose to walk or bike those trips if it was a realistic and comfortable option. We are going to have to think beyond the journey to work if we are going to build a responsive, resilient and equitable transportation system for all.