Gentrification is one of the most important — and daunting — equity issues for this generation of planners and designers. As consultants hired to bring change to communities, we are well aware that our projects can lead to displacement of longtime residents. What can we do to prevent our projects from harming the very neighborhoods and communities that are meant to benefit from them?

In her 2022 book Gentrification Is Inevitable and Other Lies, Leslie Kern seeks to change the story about gentrification’s inevitability. While gentrification has “come to seem unavoidable,” Kern argues that narrative “plays too neatly into the hands of those who benefit from gentrification.” So how can communities change the script and imagine alternative models of investment and development that deliver real benefits to people without displacing them physically or socially?

Toole Design is devoting time and resources to that question, as part of our 20th anniversary initiative to usher in a more just and accessible transportation system over the next 20 years. Of course, there will not be one solution to the problem, and some of the solutions will certainly be complex. Our goal is to share what we are learning on this topic and engage in ongoing conversations.

What is gentrification?

The term “gentrification” was coined in 1964 by sociologist Ruth Glass to refer to the “gentry” (middle-income families) moving into and renovating homes in run-down London neighborhoods. In the decades since, that gradual, household-by-household process has morphed in many places into a much more strategic, corporatized, and predictable practice of turning areas with low property values into money-making hot spots. Geographer Neil Smith explained, the greater the difference between a property’s current value and its potential value, aka the “rent gap,” the greater the profit potential for developers.

As neighborhoods gain more and different amenities and property values rise, many long-standing residents and businesses are priced out. Often, people must move further away from jobs, services, and transit options. For residents who are not physically displaced, there is often still a cultural displacement that occurs, as the character of the neighborhood changes and they no longer feel the same sense of belonging.

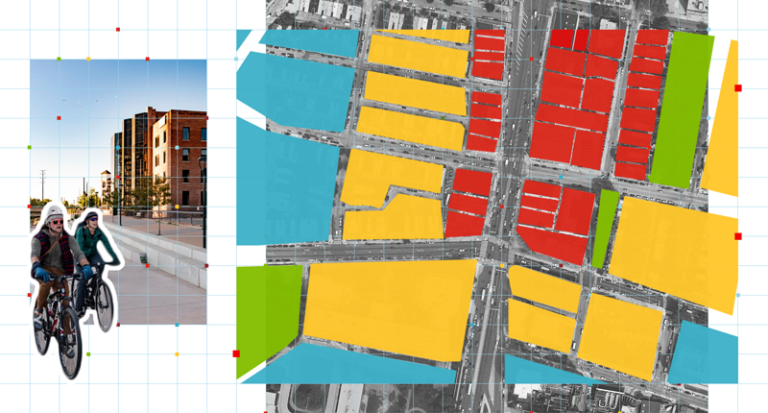

Active transportation infrastructure is one element that sometimes comes up in discussions around gentrification. Toole Design has led research on the topic, and our findings suggest that the bike lane is a symbol of something larger. It’s not about the bike lane, per se; it’s about a broader threat of change to a place that may be symbolized or accompanied by a bike lane.

It’s also important to point out that disinvestment in safety in majority BIPOC and/or low wealth communities has deadly consequences. Forcing these communities to choose between A) keeping dangerous roads without safe spaces to walk, bike, and hang out, or B) fixing those streets and risking being displaced, is a raw injustice and a false dilemma: only two paths are explored, and both are bad. Our societal complacence around unsafe and inaccessible roads has made us numb to that side of the equation — people react strongly and loudly to the threat of displacement (rightly so) but have learned to live with the threat of traffic violence because it literally surrounds them.

The right approach is to nurture a third option: fix the roads while preventing displacement. That requires a whole suite of housing and land use policies that aren’t traditionally in the skillset of transportation planners, but which we all need to learn more about and discuss during transportation projects. Furthermore, if safe roads weren’t an anomaly, then they wouldn’t have a hand in displacement — i.e., if all roads are safe, then one streetscape project isn’t likely to have an impact on property values because it isn’t a differentiator.

Attempting to break the cycle

From reading Kern’s book together, talking with staff, and gathering existing research, we have established a list of immediate actions we can all take to help change the narrative of gentrification and displacement:

- Acknowledge past harm: How have past projects contributed to gentrification and displacement in this neighborhood? We need to acknowledge these past harms, and approach future projects in a different way. That starts with listening to the community in the neighborhood, keeping people and their experiences at the center.

- Understand a place’s history: Who lives here now? Who has lived here before? It is important to document the history of the place, land, and community, and let that story inform planning efforts. We’re rethinking our approach to an Existing Conditions Assessment — a common part of most planning projects we lead — to incorporate more social and cultural history, as well as a summary of how urban renewal, redlining, and other public policies and investments have shaped who does and doesn’t live and work there today. For example, check out the Equitable Engagement Toolkit we developed with the East Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, which includes local context about Native and relocated Tribes, labor struggles and income inequalities, the present-day outcomes of redlining practices from the 1930s-50s, and more.

- Check your language: Words such as “revitalization,” “renewal,” “improvement,” and “economic development” can sound like code words for gentrification to longtime residents. Decades of infrastructure projects, many marketed using the words above, have led to displacement and other harmful outcomes in some neighborhoods. (Unsurprisingly, the people impacted are those also targeted by racism, homophobia, ableism, misogyny, and other dangerous ideologies.)

- Pay attention to who’s at the table: “Who decides, who benefits, who pays?” These are three questions that Joy Bailey Bryant urged us to consider at this year’s Smart Growth America Equity Summit. We need to be clear about our metrics for “successful” public engagement, and we need to keep asking whom the investments are for — invest for a community, not in a neighborhood. Again, keep the people (not just the project) at the center.

- Work across sectors: This was another resounding call to action at the Equity Summit — housing, land use, environmental justice, and transportation need to be part of the same conversation. As transportation professionals, we’re embracing our responsibility to also understand housing and land use policy and to routinely partner with experts from those fields in the development of our recommendations, plans, and designs. For example, as part of the Sidewalks, Crossings, and Shared Streets Plan for Austin, TX, projects located near affordable housing were given the greatest priority for implementation. Because of widespread and ongoing displacement in Austin, we focused on housing that will be guaranteed affordable for at least 5+ years and that serves people at or below 80% of the median family income level. The City’s goal was to prioritize road safety projects in places where lower income people would continue to be served by the changes over time, and to minimize the possibility that these investments could contribute to rising property values, gentrification, and displacement.

- Keep learning and sharing: These conversations are ongoing at Toole Design. We will continue to educate ourselves (and connect with others) on this important topic. We are also committed to deep engagement in the communities where we work to understand the potential for displacement.

Share your ideas

And, of course, we are interested in learning how our partners and clients are thinking about and addressing gentrification and displacement so we can all move in the right direction together. What are the most effective approaches you’re seeing or using to combat the threat of displacement in your community? Please join the conversation on LinkedIn or send us an email.