June is National Safety Month, and the “roadway safety” and “risk reduction” themes really hit home with all the work we are doing on Safety Action Plans around the country. Time and again we see four- and five-lane undivided roadways dominate the high injury networks and the list of risk factors we are tasked to address.

So this was a good time to ask one of our engineers some fundamental questions about multi-lane undivided highways in urban and suburban areas, and how roadway designers can change their approach to help reduce risks for the traveling public. Mariel Colman, a senior engineer in our Columbus office, gave us some answers.

Mariel, Five-Lane Roads Are All Over U.S. Cities and Suburbs. Are They Necessary?

No, many of them are not necessary. Much of the roadway infrastructure throughout the United States has been built (or overbuilt) to carry vastly more traffic than it actually does. According to the FHWA, “Typically, a Road Diet is implemented on a roadway with a current and future average daily traffic of 25,000 or less.” In Ohio, where I live and work, of the 44,000 miles of roadways with more than three lanes, 95% have an annual average daily volume of fewer than 25,000 vehicles, and 80% are under 15,000 vehicles per day. So even by today’s engineering standards, there is no reason these roadways need so many lanes, and certainly no excuse to further widen them.

Why are WIde Roads and Excess Capacity a Problem?

For starters, they’re a problem because they’re not safe. Wide, fast roads in populated areas are at the center of the roadway safety crisis. Yet many cities and states continue to push forward with “safety improvement” projects that involve road widening. I’m not singling out any area of the country here; nearly every jurisdiction in the U.S. historically used the same playbook and principles that prioritized speed over safety. Today, many of those same cities and states are now striving for a safer, multimodal transportation network.

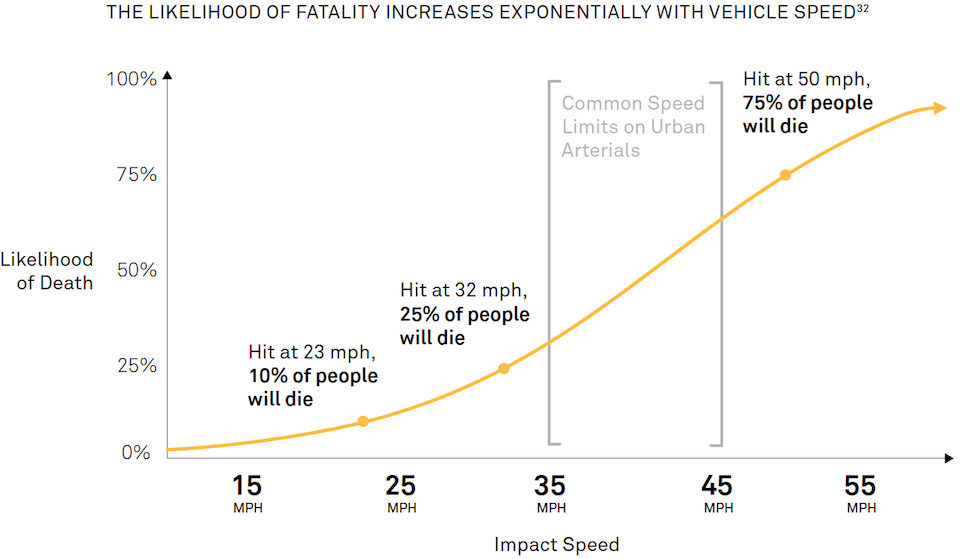

There is a body of evidence that shows wider lanes and excess roadway capacity lead to higher speeds. And speed kills. Adding travel lanes on roadways with intersections and access points means left-turning drivers have more lanes to cross. That exposes them to more potential left-hook crashes. And, since wider roads lead to higher speeds, it means those crashes are often deadlier.

Adding lanes also leads to greater exposure for people walking, biking, or rolling at intersections and crossings. This is because they have a wider roadway to cross but also because drivers need to pay attention to multiple lanes of oncoming traffic and therefore are more likely to overlook a person crossing. If we want to get serious about systemic safety, we need to design roads that invite slower speeds and are less likely to lead to fatal or serious injuries when collisions do occur.

Who are these Roads Harming?

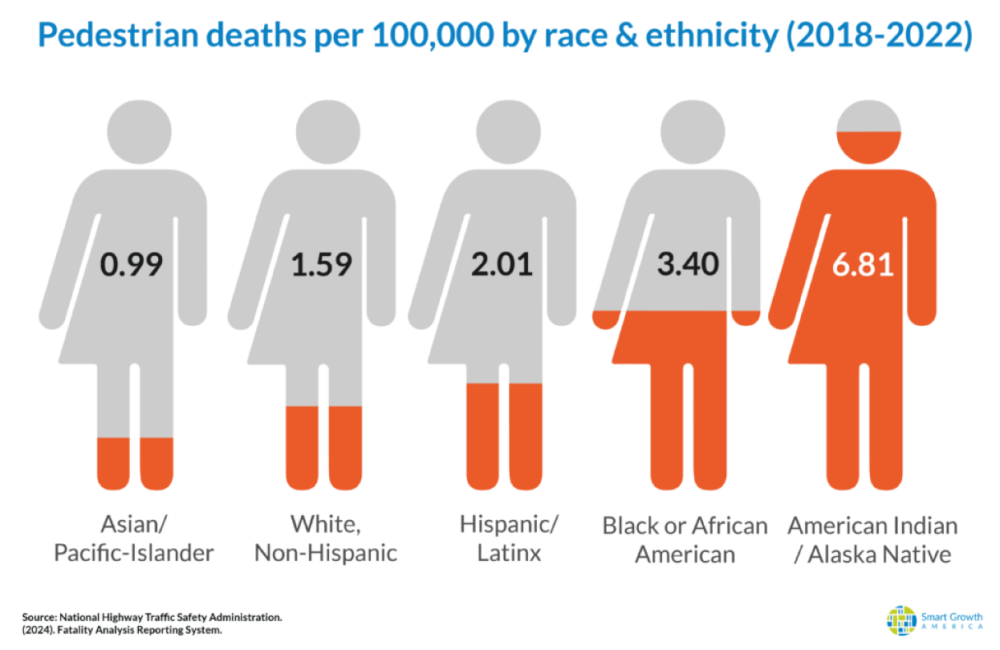

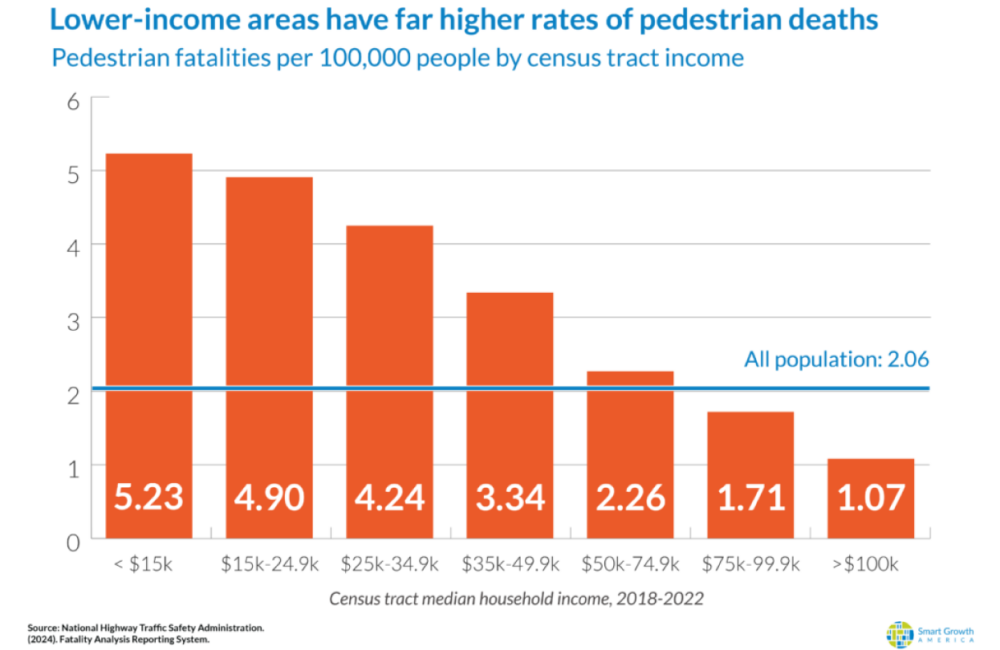

Multi-lane roadways with excess capacity perpetuate inequities in the United States. Their safety risks disproportionately harm Native American people, Black people, young people, older people, people with disabilities, unhoused people, and people from low-income households. These wide roadways with fast-moving traffic (and often minimal or no sidewalks) are more likely to occur in areas of poverty and low-wage employment. And people living and working there often lack political capital to successfully stop the construction or expansion of these dangerous corridors.

People in these areas are also less likely to benefit from a roadway designed to move cars faster, as rates of vehicle ownership are lower. Those who depend on walking, biking, or taking transit face longer crossing distances and wait times, and a high risk of exposure. These areas have effectively been deemed “flyover” zones for those with motor vehicles to pass through. And the deaths and injuries of people living and working there are the collateral damage.

Are Unsafe, Inequitable Roadways the Price We Pay for Efficiency?

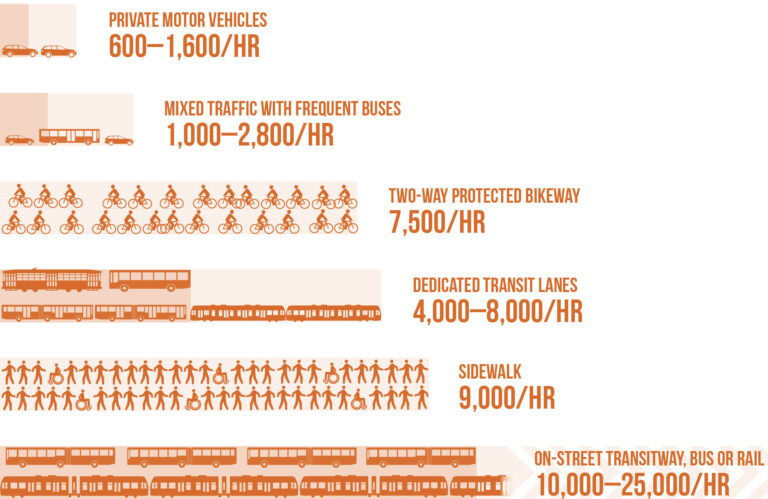

Fast-moving, multi-lane roads aren’t actually efficient. Most traffic studies focus on capacity, meaning how to move the most people in the least amount of time. But if capacity is the goal, then why are we prioritizing the least efficient mode to accomplish that goal?

Looking at the big picture, motor vehicles simply don’t move people as efficiently as other modes. We’ve all seen some version of the graphic showing how many more person-trips we can accomplish by walking, biking, or transit than by single-occupancy vehicles. Even when optimistically maxed out with 4-5 people, private vehicles can’t match the carrying capacity of shared, active, or mixed modes. If we want to build roadways that move people efficiently, let’s design them to support the most efficient modes.

I’ll also note that wide streets that prioritize motor vehicles are not an efficient use of land or of public funds. Check out Strong Towns’ article The True Cost of a Stroad for a good summary of this point.

How can Engineers be part of the solution?

In some ways, engineers are the gatekeepers of roadway design, with our codes and equations and traffic forecasting models. We have a “certified” way of predicting future traffic volumes. At the same time, I know many engineers feel trapped by these tools. I often hear things like, “We want to change what we’re doing but don’t know how.” Or “Our standards just don’t allow us to do this differently.”

Traffic forecasting is a self-fulfilling prophecy: by designing for more cars, we end up encouraging more driving. It’s a cycle based on a false assumption. More cars do not necessarily warrant more roadway space. And, crucially, more people does not necessarily mean more cars.

There is another way. What if we repurposed the extra space in the roadway for transit and bikeways? What if, instead of perpetuating inequities, we designed for modal equity, safety, and community and economic vitality?

Sounds Great… How Do We Do That? How Do We Break The CYcle?

We need to change our assumptions. We’ve already proven for decades that the assumptions we feed the model will yield results in line with those assumptions. Let’s stop clinging to outdated models that assume growth equals more cars and wider roadways. Instead, we should pledge to accommodate growth with a maximum of, say, three vehicular lanes AND high-quality pedestrian, bicycle, and transit infrastructure. We can change the equation, like Colorado is doing, and change the outcomes.

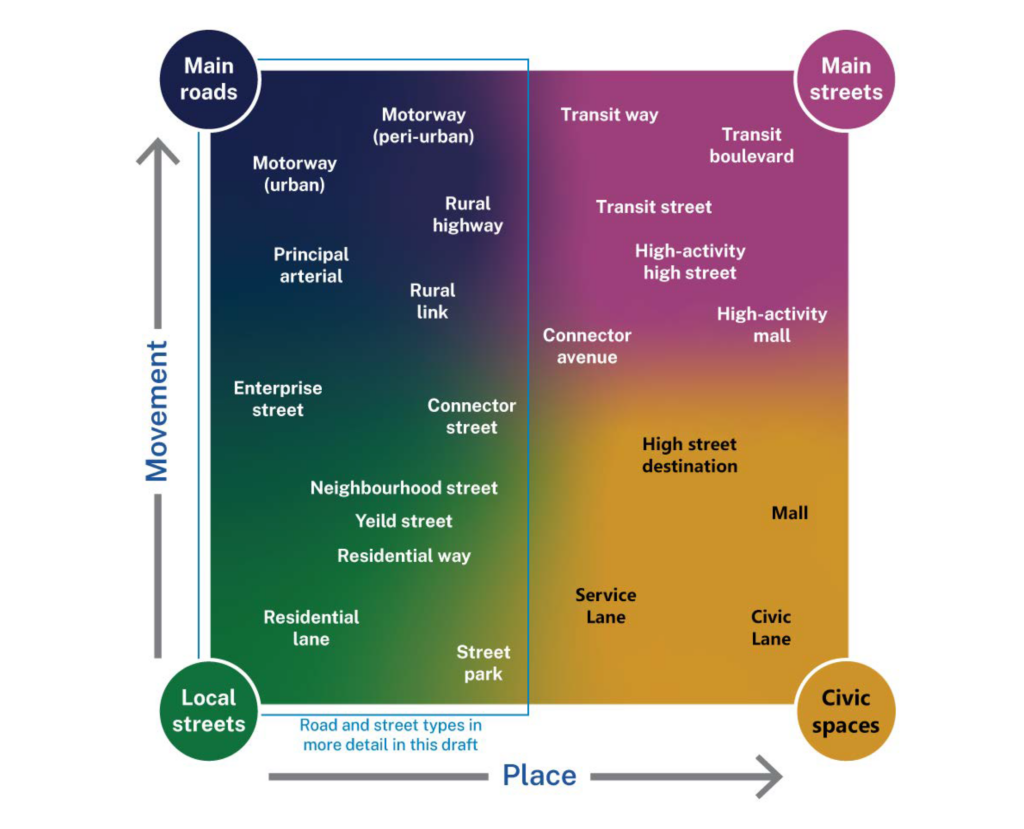

We also need to consider movement and place. Instead of starting with site selection and considering transportation needs later, we can help integrate transportation and land use decisions. I look to FHWA’s Improving Pedestrian Safety on Urban Arterials: Learning from Australasia, which outlines the Movement and Place framework used in Australasian countries and emphasizes the need for teams — including engineers — to work together to coordinate a community’s vision for transportation (movement) and land use (place), whether on a narrow city street or a higher-speed arterial.

Do You See these Changes Starting to Happen?

Thankfully, yes. Some states and communities are already taking these steps in heartening ways. For instance, the Northwest Ohio SS4A Plan features engineering and land use policies that prioritize safe access and mobility for all.

I’m really proud to work with many safety-first and people-focused engineers, both at Toole Design and in communities across the United States. We have the opportunity to rethink the standards and assumptions we have inherited to engineer a safer, more efficient, more equitable transportation future.