It’s World Landscape Architecture Month 2019 and to celebrate, Toole Design’s team of landscape architects and urban designers are taking you for a tour of our project design and implementation process. Want to learn more about how we create places for people of all ages and abilities, connect planning and design work, and turn community values into streets and shared spaces? Tune in each week for a different step in our process.

During a recent visit to a community we’re working with in North Carolina, a downtown store owner shared concerns about a new downtown master plan, which is currently in the development process. He was very resistant to the idea of narrowing street lanes and widening the sidewalk, because he needed delivery trucks to be able to reach his store. When I shared our idea of reestablishing alleys behind all the blocks downtown, he said “not on my property.” This led to him showing me plans for all the buildings he has worked on, including their facades. I eventually won him over by comparing his building façade work to the city’s desire to beautify its streets.

The most thrilling part of initiating a new project is the process of working with communities to re-imagine what a place could be. Initially, the store owner in North Carolina had difficulty understanding any other use for a street other than vehicle throughput. However, during our discussion, he was able to connect city beautification and walkability to increased business. Whether we are working on a pocket park, Main Street, or an entire regional corridor, the urban designers and landscape architects at Toole Design take pleasure in collaborating with public partners to design places that will both help people enjoy and become a part of their communities and strengthen the fabric of the built environment.

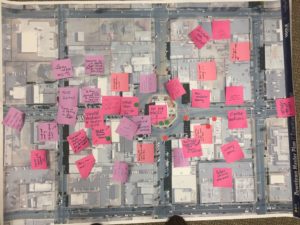

One of the first things we do when starting a project is hold an open house where we ask citizens to participate in a series of exercises that helps us understand what they value. During a community visioning workshop for Port Royal, SC, we used sticky notes to indicate on a large aerial of the community where people would like things to change. Numerous residents talked about a particular street crossing that felt unsafe, and one person noted that they would like to use a regional bike trail more often but a high-speed arterial road that ran through the middle of their town made it difficult to reach the trail. The feedback we received played a significant role in how we designed the project, leading to a safer intersection and a better connection to the regional bike trail.

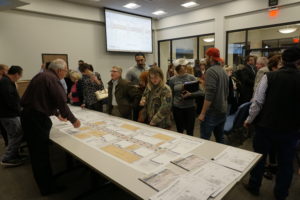

After listening sessions like these, one of the most fun and important steps is to synthesize the individual comments into overarching themes and form our guiding principles. For the downtown master plan project in North Carolina, we developed our guiding principles based on what we heard at the visioning workshop.

Our project team is in North Carolina this week to present our design ideas for the store owner’s downtown. The public review process will allow us to show residents how each design element relates to the guiding principles that emerged from their visioning workshop, which will in turn build trust between those of us working on the project and those whom it will impact most.

Engaging with community members teaches us about what makes places special. What do they have going for them? What makes them unique? What are the cultural, geographic, historical, architectural, and natural elements that contribute to the sense of place that people call home?

In Denison, TX, the historical building facades, rich music and arts culture, and historical elements all make the city unique. Our design for Heritage Park pays homage Denison’s history as the first railroad community in Texas by reflecting a round house with twelve railroad tracks embedded into the pavement. Knowing Denison’s rich arts and music culture, we designed a flush shared main street that can used for festivals and concerts.

We also often use personal narratives to communicate a project’s idea and intent to the community. For instance, when talking to parents about choosing bicycle facilities for RDA Boulevard in Atlanta, we talked about what kinds of bicycle facilities we would feel comfortable letting our own child ride.

Despite our increasingly (and digitally) connected world, it can be easy to feel isolated and lonely these days. As landscape architects and urban designers focusing on streets and community spaces, we can help counteract that by creating social infrastructure where people from all walks of life have a place to congregate and interact. Engaging with the public from the beginning helps us gauge the core values of a community and design places that reflect their unique identity.