To create tomorrow’s equitable, multimodal transportation network, planners still need to account for emotional and cultural value of cars today

Planner II, Silver Spring

My parents live off a suburban highway in Maryland, in a 1980s-era subdivision of split-level houses and tidy lawns and cul-de-sacs. Directly across the road, in a complex shaped like a giant handset phone, are the local offices of the phone company. A few years ago, my dad interviewed for a job there, and my mother excitedly told me about it the night before, saying he was glad he could work so close to home.

I asked, “Is he going to walk there?” I knew the answer before she laughed and replied: “No, he’s going to drive.”

I can picture him in a suit and tie and dress shoes, staring down the highway that divides my parents’ neighborhood from the phone company. It has a speed limit of 50mph and a traffic light where he’d have to push a button to get a walk sign, and even then, it may not come for several minutes, and on the other side, no sidewalks, a landscaped berm topped with needle-tipped bushes, and a vast parking lot with solar panels that shield the cars from rain and sun. I can imagine my dad getting mud on his dress shoes, sweat beating down on his forehead and staining his shirt collar, appearing at the front door of this office building to ask for a job.

My mother added: “He doesn’t believe somebody applying for this position should be seen walking up to the building.” Previously, my dad had an executive-level position at a big trade association in DC, and he was applying for a similar position here. He is also a black man, and he knew how this would look. So, he drove.

Your method of transportation says something about you

When we talk about active transportation, and about cities, we don’t always acknowledge the ways each mode of transportation signifies status—or the lack of status—for the person using it. For my family, which hails from both rural North Carolina (my dad) and the West Indies (my mom), cars are a physical embodiment of success. It’s not just that a car gives you the freedom to go anywhere you want, as cars are often portrayed in pop culture. It’s that owning a car, any car, shows that you have places to go. You not only have the means to buy and maintain this expensive thing, but that you can manage your money and your time. You are a successful, functioning adult.

I learned this message from an early age, growing up in a family of cab drivers and car mechanics and overall car buffs. (My first word, believe it or not, was “Isuzu.”) It’s why one of the proudest stories in my mother’s family is that my grandfather was the first Indian in his town in Guyana to own a car. It’s why when I ask my dad why he didn’t take the Metro to his old job in downtown DC, he says “I don’t want to be on somebody else’s schedule.” And it’s why my mom and my aunt conspired to get my 20-something cousin a $500 used car, even though he works at a bike shop, skateboards all over DC, and wasn’t particularly interested in driving.

This experience is by no means limited to communities of color. But in any community that has a historic legacy of not having access to wealth or opportunity, cars and the mobility they provide are still a big deal. As planners, we’ve all encountered resistance in some form to a proposed bike lane or road diet, a plan to remove parking, or even building a sidewalk. Many people may not be intrinsically opposed to these things. But their negative reactions are easier to understand if the experience of walking where they live looks like my dad’s walk through the mud to his job interview, disqualifying him as a suitable candidate for a job.

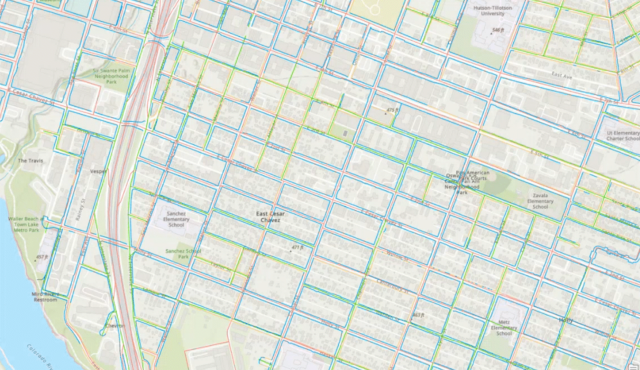

Our infrastructure tells people which modes are important – and which ones are not

When you travel on a road designed to prioritize the convenience and comfort of driving, you’re receiving a message that our communities value people who have access to cars over anyone who doesn’t. People will invest a lot of time and money to avoid feeling like they’re low-status, or that they’re not “part of the club,” especially if they’re used to not being part of the club. In North America we’ve reshaped our built environment, our culture, and our economy around driving and cars. That’s the reality we must acknowledge today.

When you travel on a road designed to prioritize the convenience and comfort of driving, you’re receiving a message that our communities value people who have access to cars over anyone who doesn’t. People will invest a lot of time and money to avoid feeling like they’re low-status, or that they’re not “part of the club,” especially if they’re used to not being part of the club. In North America we’ve reshaped our built environment, our culture, and our economy around driving and cars. That’s the reality we must acknowledge today.

The culture of driving absolutely has negative effects on our communities, our economy, and the environment. I work in active transportation because I strongly believe that creating streets where it’s safe and enjoyable to walk or bike can make our people, our communities, our economy, and our planet healthier. I want people to have lots of safe, enjoyable, and most importantly, dignified ways to get around. Nobody should feel like they must drive to gain access to jobs or opportunities or to feel like a valued member of society.

However, I remind myself that cars are also deeply aspirational for many people, as well as an economic and social lifeline for historically oppressed communities. If I talk about active transportation solely in terms of how bad driving is, I run the risk of alienating people who could be our allies.

Confronting the car culture with care

So, what does that mean for our work as transportation planners? Here’s where I start:

- Meet the communities and residents we work with where they are—to ask about their values and their goals, and to listen.

- Understand the historical context that shaped these communities.

- Demonstrate how our work can address the community’s needs and their values. For example, the project goal shouldn’t simply be a bike lane, but a safer street for all users, or improved air quality, or greater access to economic opportunities. That includes planning for people driving.

- Be explicit in showing how these projects are intended for and will benefit current residents, not future residents.

- Be willing to have honest, difficult conversations. It may be uncomfortable. But the result will be better for it.

We bring our professional expertise. The communities we work with bring lived experience and an intimate understanding of their needs, values, and goals. By working together and being empathetic to the experience of the communities we work in, we can create streets that are not only safer or more sustainable but are responsive to the public. That’s an approach that can increase community buy-in and even encourage residents to consider different travel modes.

After all, so many of us are used to a public realm that teaches you that you’re not “part of the club” unless you have a car. We need to demonstrate that streets, and the way we design streets, can actually include everyone in a community, regardless of how you get around.