Empathy

Kristen Lohse, ASLA, Principal Designer, on the power of empathy in transportation planning and design

September 6, 2019

Dive Deep into Why Empathy Matters

Earlier this summer, I was asked to talk to my colleagues at Toole Design about empathy as an element of the values-driven approach we take to our work. I pondered for many days about how I would talk to my peers about emotion and feelings.

During that time, there was a fatal shooting in Seattle’s Central District, about 1.5 miles from our office. The young man who was killed was the older brother of one of my son’s classmates. It was the fifth recent shooting at the intersection of 21st and Union.

The intersection is a neighborhood commercial center surrounded by single-family homes. Union is a two-lane collector with street trees, parking, bike lanes, and a trolley line: a lot of ingredients of a good urban street — nothing that would lead you to believe it’s been the scene of so much violence. I kept wondering why this was happening here.

The City’s response was to treat the problem as an enforcement issue and promise to increase police patrols. Meanwhile, a neighborhood blog revealed that community members had been asking for traffic calming, speed humps, and street lighting to, in their words, “transform the street and make shootouts and drive-aways less likely.” It turns out 21st Street is pretty much the only street in the area that doesn’t have any traffic calming. Everyone who lives nearby knows it’s a perfect getaway street.

Other people’s lived experiences must inform our work.

This story helped me think about empathy more clearly. Empathy is the capacity to understand by seeing, hearing, and feeling another person’s experience, from within their frame of reference, not our own. When we practice empathy and apply it to our professional decisions, we move one step closer to a built environment that works for everyone.

At 21st and Union, practicing empathy would have meant listening to what people affected by the violence were saying as well as considering solutions from outside the frame of reference of the police department. A multi-disciplinary review of the tragedy — as often happens now in Vision Zero cities after traffic fatalities — might have generated additional solutions.

There are countless examples of ways to practice empathy in our work. In a recent Insight post, my colleague Dan Reed points out that while we have good reason to believe that car dependence harms communities, many people have perfectly good reasons for wanting access to cars. In a recent project in Clinton, WA, we learned that residents were far less concerned about a proposed shared use path connection to the ferry terminal than they were about changes to the high-speed road the path would have to cross.

In each of these cases, and in all aspects of our work, if we fail to understand and value the viewpoints of the people who live in the communities we serve, our projects will exclude them and even generate opposition.

The Spectrum of Empathy

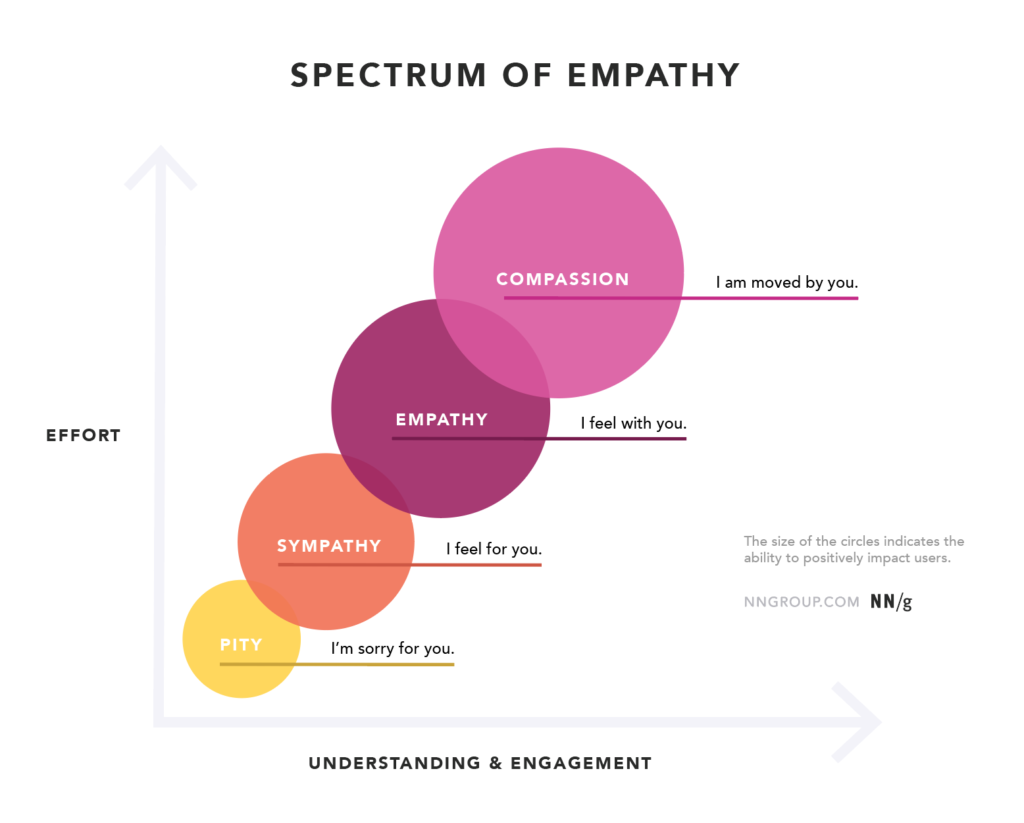

Empathy is often confused with sympathy, but they aren’t the same thing. This additional resource goes into greater detail about this important distinction.

Empathy has become a big emphasis in the field of User Experience, which focuses on understanding the needs, values, abilities, and limitations of users in the digital realm. We can learn a lot from this “Spectrum of Empathy” chart which links effort to understanding and engagement (another potential “New E,” by the way).

Sympathy is the response [e.g., to a tragedy] that requires the least amount of effort and demonstrates the least amount of understanding and engagement. Empathy and compassion require a lot more effort, show greater understanding, and result in a greater sense of connectedness.

Which brings us back to our work in the transportation industry. By demonstrating empathy, we give ourselves the opportunity to think beyond our own preconceived ideas. By talking and listening to the people who live, walk, and bike around places like 21st and Union — especially when they express their pain — we have the power and the duty to use planning and design to enact positive change. There may be more work involved, but the outcome is likely to be better, especially for the people we are serving.

Principal Designer

The New E’s Podcast

What role can emotion and understanding play in the design and construction of our built environment? Do our public spaces serve people effectively if we do not understand the needs of all the potential users? How can we orient the processes we use to plan, design, and build transportation and public space facilities to reflect the communities they will serve?

In this episode of the New E’s of Transportation podcast, Jennifer Toole and Kristen Lohse speak with Peggy Martinez, founder and owner of Creative Inclusion, about the importance of empathy in designing transportation systems that serve a community of travelers with different needs and capabilities.

Additional Resources

To Read:

Will Fanguy: 4 Essential Steps to Designing with Empathy

Interaction Design Foundation: Design Thinking – Getting Started With Empathy

Jolma Architects: Why Use Empathetic Design in Landscape Architecture?

IDEO: Field Guide to Human-Centered Design

Shawna Kitzman, AICP: Closing the Active Transportation Gender Gap